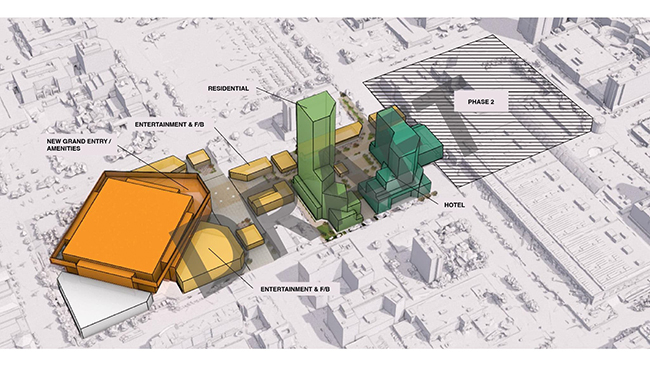

Billionaire Ryan Smith’s Smith Entertainment Group envisions a new sports, entertainment, culture and convention district in the heart of Salt Lake City. The Utah Jazz owner is seeking to renovate the Delta Center arena and the Salt Palace convention center in a multi-billion dollar mixed-use development, and Salt Lake City’s Japanese American community wants a seat at the table.

A Japanese American Hub

Japanese Americans have settled in Salt Lake City since before the war, but the city’s Japantown reached its zenith in the post-war years when many families leaving the concentration camps decided to resettle in Utah. The city was a hub for Japanese Americans during World War II as the Japanese American Citizens League relocated their headquarters there during the war and the National JACL Credit Union continues to operate out of Salt Lake City today.

The city’s Japantown, however, was decimated in the 1960s, like many other Japantowns, during urban renewal. According to Trey Imamura, a member of the Salt Lake Buddhist Temple, 93 businesses closed and all that remains of the once-bustling community today are the Japanese Church of Christ and the Salt Lake City Buddhist Temple.

In its place, the city and county built the Salt Palace, originally a basketball arena, before expanding the complex. And today, Japantown is “Japantown Street,” a single block on 100 S Street between 300 W and 200 W Streets.

Darin Mano, a Japanese American member of Salt Lake City’s city council, referred to the area as the “armpit of the Salt Palace,” on the City Cast Salt Lake podcast, describing how the ethnic enclave is nestled in a pocket of the sports and convention center complex.

Today, the Buddhist temple faces the Salt Palace’s loading docks and Japantown community members have complained that the street has become a parking lot for trucks.

“They use the space in front of our churches, basically Japantown Street as their storage for these trucks. And it makes it difficult for those who go to the churches to even get to church, because … you’ve got these huge semis on there,” Imamura told the Nichi Bei News. “It makes me scared when you have obaachan and ojiichan trying to turn and you can’t even see around the semis that are blocking the street.”

Organizing the Community

Once proposals for SEG’s new development came to light, Imamura helped organize the SLC NextGen JA group earlier this year. He invited a few Japanese American friends over for dinner to discuss what’s going on. The effort has helped bring in Yonsei and other younger Japanese American community members to learn about Japantown’s history and issues. He said around 10 members help spearhead the group, and another 10 or so members work in various committees.

“(We) just sat down at dinner one evening, and we’re like, ‘What’s going on?’ … How are we going to make sure that we’re not left out,” he said.

Dean Hirabayashi, CEO of the National JACL Credit Union and a member of the group, said he was excited for the group’s formation and leadership.

“We really didn’t know that our youth would be so active and be involved,” he told the Nichi Bei News. “They’ve taken on this project, and really have taken on a leadership role and being active in the discussions. And so, as a community, we really kind of, in a way, just kind of let them run with it a little bit.”

Hirabayashi said the first step for the group included education, as not many people in Utah knew about the history of Salt Lake City’s Japantown.

“And once they find out what’s happening there — and I’ll be honest, a lot of people didn’t even know the history of Japantown and Japantown Street in Salt Lake until all of this has happened — … they take a little more interest, and there’s been some that have become a little more active with it as well,” he said.

Identifying Issues

While word has spread and community involvement has grown, Imamura, along with other members of the Utah Japanese American community, have mixed feelings about SEG’s development. Hirabayashi said older community members remember the loss of Japantown and are cautious of what is to come, but some also feel the project could help Japantown.

Part of the agreement SEG signed with the city includes a provision to connect and activate the north side of Japantown Street with their project while “minimizing the number of truck loading and unloading areas along 100 S and facing Japantown.”

The agreement also promises a pedestrian connection to create a spatial buffer between the Japanese Church of Christ and the adjacent residential tower by creating a walkway, as well as the development of historical markers that relate to Japantown’s history.

Imamura and other NextGen members, such as Kenzie Hirai, welcome those changes, but also remain concerned about what could happen in the meantime, such as how construction could impact the annual Obon festival and Nihon Matsuri held on the street.

“I think we’re optimistic that there might be a reconnection of First South, … that’s kind of something we’d like, but that we just take everything one step, one day at a time,” Hirai said. “We’re optimistic, like I said, but we’re still just trying to secure the things we need right now, even pre-development.”

Imamura also said taller buildings, such as the high-rise residential tower across the street would also cast a shadow, and while it would likely be less of an impact to the Buddhist Temple which is across the street, he said the Japanese Church of Christ might face issues with more ice forming on the sidewalks with the added shadows cast by the buildings.

Former Utah State Senator Jani Iwamoto, a member of the Christian church, said the height was a concern for the congregation. She hopes the tower next door won’t block the light for the chapel. She said maintaining the Japanese garden the city and county installed through earlier preservation efforts Iwamoto spearheaded in the early 2000s could partially mitigate the shadows.

The garden, located on county land, also memorializes the Japantown community.

Iwamoto, however, said another major issue that has yet to be wholly solved includes SEG’s plans to convert 300 W Street adjacent to the church’s parking lot into a pedestrian walkway between the Delta Center and the Salt Palace Convention Center complex. The closure of the street would cut off the larger of the two egress points for the church’s parking lot.

“We cannot have only one access way,” she said. “We can’t go in on First South and do a U-y. We can’t survive that way. There’s no room to do a U-y unless all the cars are empty. And so we need an emergency exit and all this other stuff,” she said.

Amenable Partners

Iwamoto said the city, county and state, along with Smith Entertainment Group seem amenable to respecting Japantown’s needs. She said the developers asked the 100-year-old Christian Church if they would consider moving and she said everyone with the church opposed the idea. Despite the refusal, Iwamoto said Mike Maughan, SEG’s “right hand person,” has continued to keep in contact with the Japantown community.

“Mike Maughan has been good. He’s been good to me and I know how politics goes,” Iwamoto said. “I’m sure it would be nice if we weren’t there, … but at least they’ve been respectful enough to meet with us.”

The participation agreement also stipulates that SEG would meet at least twice a year for three years with Japantown community leaders. Iwamoto added that SEG reiterated their promise to keep Japantown apprised at their Oct. 21 meeting with the community.

Iwamoto said political leaders have also been committed to Japantown, with no recent recollection of city council members ever having opposed Japantown, and with support from both Salt Lake City’s mayor, the county and state representatives.

The Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall’s office confirmed their commitment to preserving and revitalizing Japantown to the Nichi Bei News.

“Mayor Mendenhall has prioritized working closely with Japantown’s community leaders throughout the development of the Sports, Entertainment, Culture, and Convention (SECC) District, ensuring that Japantown remains a vibrant and celebrated area,” Andrew Wittenberg, a spokesperson for the Salt Lake City’s mayor’s office, told the Nichi Bei News.

Wittenberg added that the city’s agreement with SEG ensures at least $5 million from the public benefits fund for the revitalization will go toward improvements in Japantown, “including enhancements to 100 South and the integration of Japanese architectural elements.”

Community Needs

While the Salt Lake City community may have an opportunity to talk with project leaders, it remains to be seen what exactly that participation gets them.

“There’s a lot of things that the community has access to, like all the information that is given out in city council meetings and updates and the working sessions and things like that, but there’s a lot of unknowns, and that’s what we hope to kind of get clearer and help the community focus,” Hirai said.

Hirabayashi and others said some community members would like to see a community center or a museum showcasing Japanese American history, but whether those desires are achievable is another question.

“That’s always my question, coming from a financial background, ‘how are we going to pay for that? How is that going to continue on?’” Hirabayashi said. “You just can’t build it and expect it to be run by itself. So that is a big question.”

While Imamura said Japantown Street is in the heart of the downtown project, Iwamoto also said the community is just one priority among many in the highly political multi-billion dollar effort that she estimates developers will plan to finish by the 2034 Winter Olympics slated for Salt Lake City. The project also includes the renovation of Abravanel Hall, the home of the Utah Symphony, which The Salt Lake Tribune reported would cost at least $200 million to renovate.

“We would love to just, if you could, close your eyes, just have a vibrant Japantown again,” Iwamoto said.

Failing that, she would like the new development to incorporate some of Japantown’s culture and history. Imamura shares this outlook.

“Whatever that looks like and the roadmap to get there, I’m not 100% sure, but I would say for me to have a street that is based on our culture and puts our culture and our community first, is what I’m advocating for, and to also make sure that the memory and all the efforts from the Issei and the Nisei and the

Sansei, just basically the previous generations, make sure all of their efforts and their legacies are honored in this next step for our community,” he said.

For more information on the proposed project, visit https://capital-city-revitalization-zone-slcgov.hub.arcgis.com and https://reimaginedowntownslc.com.

Tomo Hirai is a Shin-Nisei Japanese American lesbian trans woman born in San Francisco and raised in Walnut Creek, Calif., where she continues to reside. She attended the San Francisco Japanese Hoshuko (supplementary school) through high school and graduated from the University of California, Davis with degrees in Communications and Japanese, along with a minor in writing. She serves as a diversity consultant for table top games and comic books in her spare time.

Leave a Reply